Overview of .NET Ecosystem in 2015

- Introduction

- A 10,000 foot view

- From the bottom up

- Runtimes

- .NET Main workloads and consumers

- Tools

- More resources

Introduction

.NET Ecosystem is undergoing a major shift and restructuring in 2015. As with any major shift, there are a lot of “moving pieces” that need to be tied together in order for this new ecosystem and all of the recommended scenarios to work. This short overview should help you get a grasp on what are these moving pieces, how do they fit together and what is the goal of each one.

This document does not assume any knowledge of .NET, so if you are encountering the framework for the first time you should be fine. If you already met and are working with .NET Framework, this document will allow you better understanding of what is new and how are things changing.

A 10,000 foot view

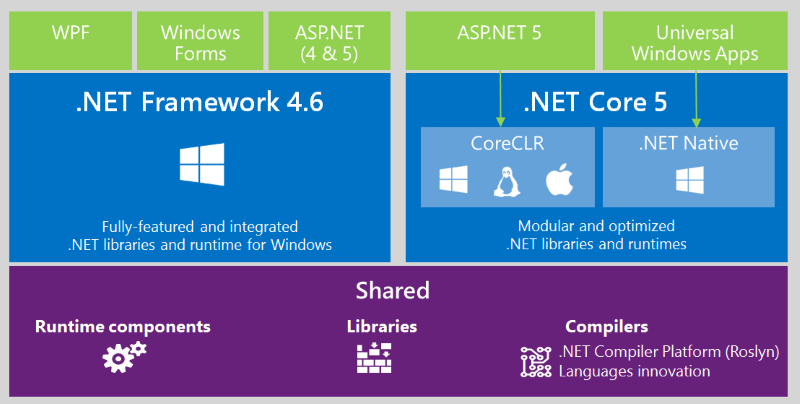

Let us start from a very high-level view and illustrate the major working parts of the new .NET ecosystem, and then start delving into each one in more detail. The diagram bellow illustrates the shared ecosystem as it exists, or will exist, in 2015.

As we can see, this is a very vibrant and diverse ecosystem. If you are coming from a .NET background, it will also be very different to what you’ve used to. So let’s start explaining each bit in more detail.

From the bottom up

Let’s start our exploration from the bottom most layer of the above diagram.

.NET Compiler Platform (“Roslyn”)

Roslyn is the codename for the new .NET Compiler Platform. The idea behind Roslyn is to allow a much more open access to the entire compiler pipeline. Previously, the compilers have been treated as “black boxes”. Source code comes in, magic happens, compiled code comes out. During that process, a compiler finds out a lot about your code, however, for the most part, you care only about the end product, runnable code. Therefore, so far we preferred that arrangement.

However, modern requirements of a more agile approach to code building have uncovered a need for next generation of tooling, one that would allow better experience when coding through applying the knowledge that compiler has to create new versions of Intellisense, code analyzers etc. Providing this hsa been the driving principle behind starting the .NET Compiler Platform project.

Essentially, Roslyn is the .NET compiler written in managed code and surfaced to consumers as a set of DLLs. This is also known as “compiler as a service” approach, in which you can instantiate and use the actual compiler in your code. This is the way Visual Studio 2015, for instance, provides Intellisense and other facilities.

The .NET Compiler Platform is one of those topics that you can spend a fair amount of time and space writing about; however, going deeper would be beyond the scope of this overview. However, fear not, the team has assembled a great Roslyn overview document that you can peruse to get more information.

Runtimes

Above the shared components, we can see several runtimes being referenced. Time to dissect those.

.NET Framework 4.6

The tried and true workhorse of the past 10+ years, the full .NET framework is still around, of course, and has been recently updated to version 4.6. There are many enhancements to the CLR (the runtime) and the BCL (the class library) that comes with this release for the consumers presented in the diagram above, such as the .NET Compiler Platform, new language innovations etc.

This edition of the .NET Framework is not cross-platform and you can run it only on Windows. Most of the consumers of this particular edition of the .NET Framework should be already know, if in name only. Windows Presentation Foundation or WPF is a framework for building desktop applications using specific technologies to make them compelling and rich. Windows Forms is already known as the bulwark of the LOB desktop applications from the early day of the .NET Framework. Of course, ASP.NET is Microsoft’s main web stack, which is getting a major overhaul in the 5 release timeframe.

.NET Core

.NET Core is a cloud-optimized, pay-as-you-go, cross-platform port of the .NET Framework. The roadmap currently in place covers support for three main operating systems, Linux, Windows and OS X. The community porters have made it work on FreeBSD as well. It is freely available on GitHub and it is very easy to get for the supported systems and get going.

The best way to explain what .NET Core is about is to contrast it with its “cousin”, the .NET Framework, pictured above. When you install .NET Framework, you get not only the runtime, but also the entire Base Class Library (BCL) with it. It is installed centrally in a known location in Windows centrally so all programs can use it, and the libraries that come with it are also centrally available. Any .NET application that is ran on Windows can thus expect a certain level of support, depending on the actual version the machine it is being ran on has installed.

This may seem like an excellent idea, mostly because it is. However, there are those scenarios, like the ASP.NET 5 one which we will look at below, that really do not fit well with this approach. We wanted to enable developers to make their solution fully packaged and isolated on a machine where it needs to run. That means, for instance, that when you deploy your application, you want to be in full control of the runtime, library versions and other things your application depends on.

This is precisely why .NET Core came into the world. First, it is a completely componentized framework, meaning that everything is available as a package that you can opt-in. This includes the entire list of libraries that you would use in your application; you pull them in via packages and ship them as part of your application, and then update them as you see fit, without messing around with the centrally installated version. This makes it that much easier to deploy your apps in the cloud, Docker images or even hosting the runtime yourself if you’re so inclined.

The above also means a much different development experience than what was previously standard norm.

.NET Native

Before we can explain what .NET Native is all about, we need to first cover some (very basic) ground on how .NET runtime currently executes code. The way .NET framework normally works is by JIT-ing IL (Intermediate Language) code. This happens at runtime. For the new generation of mobile and tablet applications, however, there are many scenarios where this is not really optimal, and where the developer would like to get to the actual code that is being run, without all of the JIT-ing and other things.

Enter .NET Native. It is a toolchain which is focused on compiling the IL code into native code. It is also known as AOT, Ahead of Time compiler, to differentiate between it and the Just in Time compiler, or JIT.

.NET Main workloads and consumers

Each of the runtimes above can be used on their own, for instance in console applications or similar. However, each of them have been the building block of a major consumer, or a workload on top of it. The two main workloads are ASP.NET 5 and Universal Windows Platform apps.

ASP.NET 5

ASP.NET 5 is a completely reimagined way of working with web applications on the Microsoft application platform. There are many new things that will come with this new realease; too much to go into detail here. ASP.NET 5 will be cross-platform, allowing you to run web applications written for it on Linux, OS X and Windows.

ASP.NET 5 can use either the Core CLR or the full, desktop .NET Framework to run, depending on the need. It also has a completely revamped approach to tooling, where it is starting with a “CLI first” philosophy, thus allowing one set of tools to be used on different platforms.

But most importantly, it also allows a pay-as-you-go model, in which you only include in your web application what you really need. There is no more “packaged also” mode, where you have to struggle with large assemblies that cut into your request size and this eat into your performance. With the new approach, you will be able to use only what you need/want.

Universal Windows Platform apps

When you create a Universal Windows Platform (UWP) app, you’re creating an app that has the potential to run on any Windows-powered device:

- Mobile device family: Windows Phones, phablets

- Desktop device family: Tablets, laptops, PCs

- Team device family: Surface hub

- IoT device family: Compact devices such as wearables or household appliances

Each UWP app is using the .NET Core as its runtime and .NET Native as its default toolchain. You can find more about it in the resources section below.

Tools

Of course, in order to help developers work with the new runtimes, there are tools available for all scenarios from running an application to packaging it and deploying it. Though they are not present on the above “10k foot view”, tools are a very important piece of the developer’s life.

.NET Version Manager (DNVM)

DNVM is a a command-line utility that allows you to install and use various “execution environments” on any machine. It runs on Windows, OS X and Linux.

It works by using predefined feeds to download the runtimes, place them in a well-known location and add environment variables for the user to be able to use them. It also allows you to list them out, switch between currently installed runtimes for the next invocation etc.

The DNVM is an important piece of the development flow. It is the first step you do when setting up your development environment. Think of it as a “apt-get” or Homebew for .NET runtimes, and you would be very close.

.NET Execution Enviornment (DNX)

DNX refers to one of the execution environments that the DNVM installs. Each DNX is an isolated and self-contained unit. This means that you can have tens of DNX-es installed either on your machine or on the target machine and they will never interfere with one another.

DNX consists of two major parts: the actual DNX and the DNU (DNX NuGet Utility). DNX is used when you want to run the code you’ve written. If you go to the getting starteg page on this site, you will see in all examples last step is invoking the currently active DNX to run the code in a given directory. It will compile the code and run it, so there is no reason to invoke the compiler. DNX does this by using “Roslyn” described at the beginning of the document.

The other important part is the DNU, which is used to retrieve the packages that are dependencies of any given application. Each .NET Core application will have its dependencies listed out in a project.json file, which lives together with the application’s code. Using DNU, the programmer is able to get these dependencies and run the code. DNU also supports more scenarios, namely transforming your code in a package as well as making it ready to be published on the remote server.

Coupled with DNVM described in the previous section, DNX and DNU make up a major chunk of the developer’s workflow in the .NET world of 2015 and beyond. You can read more about these tools at the DNX official documentation.

Visual Studio

Visual Studio is Microsoft’s primary IDE and programmer editor. It is an incredibly rich and powerful IDE that offers a slew of features for modern development. It runs only on Windows.

Visual Studio Code

Visual Studio Code is a cross-platform editor that is oriented towards supporting writing modern web and cloud applications. It provides a subset of features that have made its “older brother”, Visual Studio, so popular, like Intellisense and strong debugging support. It is probably the easiest way to get started with ASP.NET 5 development on Linux and OS X.

More resources

This was a very basic overview of all the “moving pieces” that are a part of the current .NET ecosystem. Hopefully, you now have a somewhat deeper understanding of the relationship and each piece of the ecosystem. Still, there is lot more to cover. Use the resources in the list below for further discovery and learning.